Accidents that involve nuclear weapons inevitably draw attention as they remind us that the nuclear enterprise is inherently dangerous. There is a good argument that nuclear operations are prone to what Charles Perrow called normal accidents. Scott Sagan covered nuclear weapons in detail in his book "The Limits of Safety." The book, of course, looked at US accidents and the lessons learned from US nuclear operations. It would be interesting and valuable to compare it to the Soviet and Russian record.

Accidents that involve nuclear weapons inevitably draw attention as they remind us that the nuclear enterprise is inherently dangerous. There is a good argument that nuclear operations are prone to what Charles Perrow called normal accidents. Scott Sagan covered nuclear weapons in detail in his book "The Limits of Safety." The book, of course, looked at US accidents and the lessons learned from US nuclear operations. It would be interesting and valuable to compare it to the Soviet and Russian record.

As one can expect, there is not much information about Soviet and Russian accidents. But there is some. I tried to collect these bits in a working paper that was prepared for a workshop "Nuclear Crises Revisited" organized by the Managing the Atom program in February 2024. Managing the Atom will eventually publish all contributions as a book, which will cover many other accidents and nuclear crises, from US false alarms to Berlin in 1961 and US-North Korea in 2017. It will be a very interesting volume.

My paper covers early nuclear weapons handling arrangements, Soviet approach to command and control adopted in the early 1970s (with the reliance on a deep second strike and then on a launch from under attack). Of course, I look into the 1983 Colonel Petrov accident and the 1995 Black Brant event. There were other accidents as well, for example, Soviet Union's own "training tape" incident in 1978, in which an early-warning center in the Far East (most likely Mishelevka) was showing a visiting party boss how the system operates. There was also a noteworthy event in 2013, with an Israeli Arrow test. My overall conclusion is that a reasonably good design of the command and control system and the assumption that a bolt out of the blue attack is highly unlikely can go a long way to preventing the worst.

I also look at some known accidents in which nuclear weapons could have been damaged. As far as we know, these were fairly rare. If you compare it to the US record, it is clear why. Unlike the United States, the Soviet Union apparently had never flown its bombers with nuclear weapons on board. Nuclear tests in which weapons were delivered by an aircraft were, of course, the exception, but in those the bomber would land empty. One known incident is the aborted test of the first thermonuclear bomb, RD-37, in November 1955. Because of the weather conditions the Tu-16 bomber had to land with the weapon on board, which almost gave everyone involved in the test a heart attack. This may have been the only landing with a live nuclear weapon on board. At least I haven't seen anything that would suggest otherwise.

Not surprisingly, the majority of accidents happened with naval weapons. The Soviet Union lost three submarines with 25 weapons on board. Loading operations, of course, were particularly dangerous. There was a missile fire in Vilyuchink in September 1976, in which a warhead of an R-29 missile was sent to the bay by an explosion. I also have oral accounts of other incidents. In one, a torpedo (or a cruise missile) was accidentally launched during loading on a surface ship. It safely landed on the other side of the bay (it was one of the Northern Fleet bases). In another loading (or, rather, unloading) incident, a missile caught fire while being handled by a crane. This apparently happened some time in the 1990s. I didn't include these in the paper since I couldn't find a documented account of these events.

There is also no direct evidence of the severity of the 2011 fire on the Yekaterinburg submarine. But the circumstantial evidence is fairly strong - it appears that the submarine had missiles (with nuclear warheads) on board at the time it caught fire.

The Rocket Forces had their share of accidents as well, although not nearly as many as the navy. There were two explosions of UR-100/SS-11 missiles in silos in 1967. Other than that, there are no accounts of problems with ICBMs. Interestingly, there have been no reported serious accidents with mobile ICBMs, although there have been accounts of launcher rollovers. I think there is even a photo of it somewhere.

Of course, it would be good to have a detailed official account of the accidents. But even what we have allows us to draw some conclusions. The main ones are: think about your command and control procedures, don't keep your nuclear forces on hair-trigger alert, don't move nuclear weapons around. Ideally, just put them in some bunker under lock and key, but we are probably rather far from this solution.

Image: Fire on the Yekaterinburg submarine in December 2011. Posted on the airbase.ru forum.

The Air and Space Forces conducted a successful launch of a Soyuz-2.1b rocket from the complex No. 43 of the Plesetsk space launch site (Ministry of Defense video). The launch took place at 21:59 MSK (18:29 UTC) on 5 February 2026. The rocket and its Fregat boost stage delivered into orbit nine satellites.

The Air and Space Forces conducted a successful launch of a Soyuz-2.1b rocket from the complex No. 43 of the Plesetsk space launch site (Ministry of Defense video). The launch took place at 21:59 MSK (18:29 UTC) on 5 February 2026. The rocket and its Fregat boost stage delivered into orbit nine satellites.

The satellites are likely to receive designations from Cosmos-2600 to Cosmos-2608. Their international designations are 2026-023A to 2026-023J, numbers in the NORAD catalog are 67674 to 67682.

As of 9 February 2026, the only satellite identified by the US Space Command by name is Cosmos-2600. It is deployed in a sun-synchronous orbit with the altitude of about 325 km. Remaining eight objects were deployed in two groups, in orbits with the altitude of about 500 km.

The satellites' missions are not immediately clear.

New START, the treaty that limited US and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals, will expire on 5 February 2026. So, what will happen next? This post tries to outline some scenarios of how the United States and Russia could respond to the treaty expiration. None of these are truly optimistic, but some are less pessimistic than others.

New START, the treaty that limited US and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals, will expire on 5 February 2026. So, what will happen next? This post tries to outline some scenarios of how the United States and Russia could respond to the treaty expiration. None of these are truly optimistic, but some are less pessimistic than others.

To recap, the treaty was signed on 8 April 2010, entered into force on 5 February 2011, and then extended for a full five years in January 2021. The extension was done by an exchange of notes between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the US Embassy in Moscow on 26 January 2021. Russia ratified the extension by a Federal Law, which entered into force on 3 February 2021. In February 2023 Russia announced that it suspends the treaty. The United States protested, pointing out that the treaty does not have a suspension option, and later retaliated, suspending data exchanges and other activities.

In September 2025, the Kremlin announced that

Russia is prepared to continue observing the treaty's central quantitative restrictions for one year after February 5, 2026.

The United States has not responded to this offer one way or another. President Trump said at some point that it was a good idea, but in a January 2026 interview said that "If it expires, it expires. We'll do a better agreement."

The main reason the United States has not responded to the Russian offer is that the US expert and political community has essentially reached consensus on the need to expand the US strategic arsenal. The arguments are China's buildup, "the two-peer problem," Russia's record of non-compliance, and optimism about winning arms races. The strength of these arguments can be debated, but at this point the momentum to ditch New START limits is very much unstoppable.

Nevertheless, there are options. The most optimistic one is that the United States will accept Russia's offer and will commit to adhere to the New START limit for one year. It is, however, extremely unlikely that the United States will do so, unless, of course, this would be a decision coming directly from President Trump. Still unlikely, but not impossible.

One problem with accepting the Russian offer as it stands is the absence of verification. It's not that the United States is in the dark about the status of the Russian forces, at least to the extent that matters. But verification is an important symbolic element of a treaty that can signal how serious a state is about its obligations. Ideally, the United States would make a counteroffer and suggest that it would be willing to stay within the treaty limits if Russia agrees to resume some verification activities. Data exchange and notifications, for example. On-site inspections would be even better, but these require a formal treaty, mostly because of the immunity for inspectors and other issues like that. But data exchanges are doable without a treaty. My guess is that Russia would refuse to resume anything, but it is worth trying. It's a reasonable ask and the United States could point at it as a sign of good-faith effort.

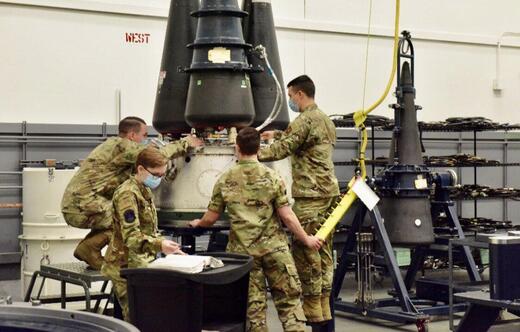

On the pessimistic side of the spectrum, the United States will declare that it is free from any constraints and proceed with what is known as "upload" - returning reserve warheads to its missiles. The US "upload potential" would allow it to increase the number of deployed warheads from the New START 1550 to about 3500 (here is a good post by the FAS team).

There are options within this pessimistic option too. For example, the United States can do the upload openly and report (with some accuracy) how many warheads have been returned. Or it can just keep everyone in the dark about its plans and specific upload steps. I hope that since the upload would be a largely symbolic step aimed at China, the plan will be made public, but it might not.

One interesting option, which is somewhere in between, is that the United States will note the end of the treaty, say that there are no obligations anymore, but then neither proceed with the upload nor say publicly that they will stay within the treaty limits. So, the Russian offer will be accepted but silently. This could create an interesting challenge for Russia, which would then have to decide how to react. I don't think this scenario is particularly likely, unless there is some kind of internal disagreement about what to do. But the United States can postpone any announcement until at least the NPT PrepCom session in May 2026.

As for Russia, I would expect that it will confirm its offer and pledge to adhere to the treaty limits for at least one year no matter what the United States does. There is really no downside for Russia in doing so. It would get to show itself "a responsible nuclear power," which could come in handy at the NPT PrepCom meeting and in other contexts. Then, in February 2027 Moscow would reluctantly say that it has no choice but to follow the United States. But it's not like Russia needs more warheads.

I don't think we can avoid the scenario in which the United States goes for upload. But as for the announcement of the decision, we will probably have to wait. One can announce the decision to go for an increase later, when the wave of anxiety about the end of a major arms control agreement has passed. On the other hand, the opponents of the limits extension rightly worry that if they let the 5 February 2026 moment pass, it will be more difficult to justify the buildup later on. This is probably the main reason the opposition to the Russian offer is so strong - the opponents don't want to let people get used to the idea that one may not need a treaty to keep the number of nuclear weapons under control.

Image: Personnel at Minot AFB demonstrate the capability to return a Minuteman III missile to a three-warhead configuration during a snap exercise in July 2020.

Forty years ago, on 15 January 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev announced a plan to eliminate all nuclear weapons by 2000. The next day, the Ministry of Defense and the Foreign Ministry held a joint briefing, at which Georgy Kornienko (First Deputy Foreign Minister) and Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev (Chief of the General Staff) presented the plan. (And I think I was watching it live on Soviet TV.)

Forty years ago, on 15 January 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev announced a plan to eliminate all nuclear weapons by 2000. The next day, the Ministry of Defense and the Foreign Ministry held a joint briefing, at which Georgy Kornienko (First Deputy Foreign Minister) and Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev (Chief of the General Staff) presented the plan. (And I think I was watching it live on Soviet TV.)

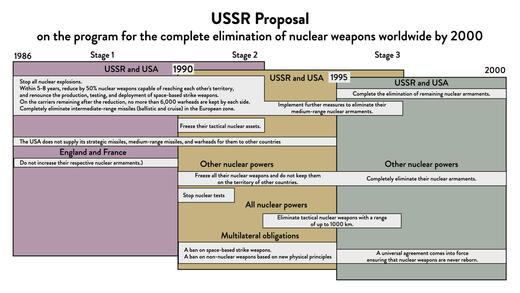

The image above is, I believe, a photo of the poster that they used during the briefing. The poster is not quite a masterpiece of graphic design, but it's generally in line with the style common in the Soviet military. (The English design below was put together by Alex Glaser.)

The origins of the plan are quite interesting and even Soviet participants of the event disagree on whether it was just a propaganda move or a serious proposal. My take is that there was a bit of both, but it was definitely an attempt to step back from confrontation. It's worth noting that the proposal took its final form after the first Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Geneva in November 1985, but before the Reykjavik meeting in October 1986.

Of course, many members of the Reagan administration were deeply skeptical about all this (to put it mildly). However, George Shultz saw it differently. Here is how he described his conversation with the president the day when they learned about the proposal:

I said to President Reagan, "This is our first indication that the Soviets are interested in a staged program toward zero. We should not simply reject their proposal, since it contains certain steps which we earlier set forth." The president agreed. "Why wait until the end of the century for a world without nuclear weapons?" he asked. He recalled that he had, in fact, made that statement to Gorbachev in the pool house at Fleur d'Eau [in Geneva].

The plan suggested disarmament in three stages:

Stage 1 (1986-1990): The United States and the Soviet Union would stop nuclear testing, reduce their strategic nuclear arsenals by 50% (leaving no more than 6000 warheads), eliminate all medium-range missiles in Europe. The United States commits not to transfer their strategic and intermediate-range missiles and their warheads to other states. The UK and France would freeze their arsenals.

Stage 2 (1990-1995): The United States and the Soviet Union continue the elimination of their intermediate-range missiles and take the process further (maybe to Asia?). They also freeze their tactical nuclear arsenals. Other nuclear powers would join the process. Other nuclear states (presumably the UK and France) would freeze their arsenals and commit not to deploy their weapons on the territory of other states. They stop all nuclear tests. All nuclear weapon states (not clear if it was meant to include China) would start the elimination of all tactical weapons with the range of less than 1000 km (this process was expected to continue after 1995). In addition to this, there will be a multilateral agreement to ban strike weapons in space and on non-nuclear weapons based on new physical principles.

Stage 3 (1995-2000): The United States and the Soviet Union complete the elimination of all remaining nuclear weapons. Other nuclear weapon states eliminate their nuclear weapons as well. At the end, a universal agreement comes into force ensuring that nuclear weapons are never reborn.

Of course, the plan was not realistic. But on the other hand, a lot of its elements became reality: the INF Treaty, START, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Even the UK and France ended up not just freezing but actually reducing their arsenals. So, I guess it pays to be bold.

Getting a good estimate of the status of Russian strategic nuclear forces has become very difficult after Russia suspended the implementation of New START in February 2023. The last data exchange reflected the status of its forces on 1 September 2022. Russia declared having 1549 deployed warheads, 540 deployed launchers, and 759 total launchers.

Getting a good estimate of the status of Russian strategic nuclear forces has become very difficult after Russia suspended the implementation of New START in February 2023. The last data exchange reflected the status of its forces on 1 September 2022. Russia declared having 1549 deployed warheads, 540 deployed launchers, and 759 total launchers.

The FAS team, of course, continues to publish their estimates - they remain the best source for all nuclear-related numbers. I have used their estimates, of course, but my take may be a bit different.

The biggest question is the status of the ICBM force. Or, rather, of its silo-based part. More precisely, the question is, what is happening with SS-18/R-36M2, which is responsible for a substantial portion of Russian strategic warhead count.

With other missiles, the situation is reasonably non-controversial - Russia completed the withdrawal of old SS-25/Topol mobile missiles in 2023 and now operates seven divisions with 18 to 36 Yars missiles each. The only exception is the 54th missile division in Teykovo, which has 18 Topol-M and 18 Yars ICBMs. So, it's a total of 18 mobile Topol-M ICBMs and 180 mobile Yars. The former are single-warhead, the latter are believed to carry four warheads.

In addition to mobile Yars ICBMs, Russia has been deploying some in silos. This deployment began in Kozelsk in 2014. At the end of 2025, the Rocket Forces announced that the deployment in Kozelsk has been completed. The division now has 30 missiles of this type.

Yars missiles are now being deployed in Tatishchevo as well. According to the commander of the Rocket Forces, the first regiment began combat duty there in 2025. It does not seem that the regiment has the full complement of ten missiles yet, though.

It is not clear if Yars missiles are replacing silo-based Topol-M ICBMs that are deployed there. The deployment in Tatishchevo started in 1997 and was completed in 2012, with 60 missiles placed in silos. It appears that all these missiles are still in service. The oldest Topol-Ms are about 27 years old and we know from the SS-25/Topol experience that even though it's close to the limit, these missiles can probably stay in service a bit longer. The last firm data on Topol was that its service life was extended to 26 years, but in the end they stayed in service for closer to 30, retiring in 2022-2023.

Now the difficult part - the missile divisions in Dombarovskiy and Uzhur. What we can say with certainty is that there are 12 Avangard systems deployed in Dombarovskiy (coordinates of Avangard silos are in this post). These are older SS-19/UR-100NUTTH missiles that carry one hypersonic glide vehicle each.

In addition to this, there are three regiments, with six silos each, of SS-18/R-36M2 missiles in Dombarovskiy. The silo positions seem to be intact, but it's hard to tell if there are missiles there and what is the status of these missiles.

A similar question can be asked about the division in Uzhur. The division has 28 intact silos, six of which are being modified to deploy Sarmat (see the FAS post for more detail and images).

The plan for Sarmat appears to be to deploy 46 missiles, so all R-36M2 silos at Dombarovskiy and Uzhur would be used for Sarmat. The Sarmat program, of course, has encountered some serious problems, so it will not be ready for deployment for some time.

The question is then, are SS-18/R-36M2 missiles still operational? The deployment of this version of the SS-18 missile began in 1988 and the youngest of them, produced around 1992, are more than 33 years old now. Back in the day, in 2010, the Rocket Forces were somewhat optimistic about extending the lifetime of the missile to 33 years, but later said it would only be 30.

Strictly speaking, for a system with no moving parts, which an ICBM sitting in a silo essentially is, life extension can be done by adjusting the reliability of the system. Yes, by the end of, say, the fifth decade only a small fraction of missiles would be able to start, but how do we know how many? Normally, of course, these things are confirmed with regular flight tests, but R-36M2 hasn't been flight tested for more than a decade. The last record that I can find was a launch during an exercise in 2013. Another option is to closely monitor the health of a missile without tests. One of the problems here is that the R-36 missile line was produced in Ukraine and this kind of evaluation would be rather difficult without Ukrainian experts (although maybe not impossible). In better times, in 2008, Russia and Ukraine, in fact, agreed to do just that. Needless to say, this kind of cooperation became impossible after 2014. Indeed, it may not be a coincidence that there were no R-36M2 launches after 2013. [UPDATE: Colleagues reminded me that the are moving parts - R-36M2, unlike its predecessors, was kept in the high degree of readiness, with its gyroscopes spun up.]

One data point here is the R-36M2 predecessor, R-36MUTTH. Missiles of this type were deployed in 1979-1986. They have been gradually withdrawn from service, but some were used as space launchers, known as Dnepr. The last Dnepr launch took place in 2015, so the missile was about 30 years old. This suggests that 30 years is not a limit for R-36M family of missiles. However, it does not tell us anything about the possibility to extend the lifetime beyond that.

One problem is that if all R-36M2 ICBMs remain in service with their nominal load of ten warheads per missile, there is no way Russia could have complied with New START limits. Together with newer missiles, like Yars and Topol-M, ICBM warheads alone would almost reach the New START limit for the total deployed warheads (1370 vs. 1550). But that's if R-36M2 missiles are deployed. My take is that they are not. Indeed, if we assume that the silos in Dombarovskiy and Uzhur are empty, we will get quite close to the 540 deployed launchers Russia declared in 2022.

This means that as of early 2026, Russia has 112 silo-based ICBMs (Topol-M, Yars, and Avangard) and 198 mobile ICBMs (Topol-M and Yars). It's worth noting that there seem to be different versions of Yars, sometimes referred to as Yars-M or Yars-S. It's quite difficult to tell, however, whether these are deployed and where.

How many warheads these ICBMs carry is a different question. To stay within New START limits, Russia had to "download" some (or even all) of its MIRVed missiles, ICBMs as well as SLBMs. More about it at the end of the post.

Submarines are much easier to count. After Knyaz Pozharsky was accepted into service in June 2025, Russia has eight submarines of the Borey and Borey-A (Project 955 and 955A) class. Each of these carries 16 Bulava SLBMs, so the total is 128 Bulava missiles. There are also five older submarines of the Project 667BDRM/Delta IV class, each with 16 R-29RM (Sineva or Liner) missiles. In addition, one Project 667BDRM submarine is in overhaul. The last submarine of the even older Project 667BDR/Delta III class, Ryazan, was withdrawn from service some time after 2021. This means that the total number of deployed SLBMs is 208. They can carry up to 1088 warheads, but as is the case with ICBMs, they probably carry fewer.

The air-based leg of the strategic triad had a rough year. The FAS team estimated that at the beginning of 2025, Russia had 52 Tu-95MS aircraft and 15 Tu-160/Tu-160M. However, some aircraft were lost in the Pautina/Spiderweb operation carried out by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) on 1 June 2025. The operation targeted airbases with Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 bombers. The exact number of Tu-95MS aircraft lost that day is unknown, but it has been estimated that ten Tu-95MS were destroyed.

Now to the number of warheads. We know that Topol-M is a single-warhead missile. Avangard is also considered to be a single-warhead missile. Each strategic bomber is counted as one warhead. As for MIRVed ICBMs and SLBMs, it is believed that the nominal load of Yars is four warheads, Bulava can carry six warheads, and R-29RM - four. Had all missiles carried their full load, the total number of deployed strategic warheads would have been 2115, which is way over the New START limit of 1550. One explanation, of course, is that Russia does not comply with this limit, but I do not believe this is the case (I know that there are many people who would happily insist that it is, but that's a discussion for a different post).

A more realistic option, in my view, is that MIRVed missiles do not carry a full load of warheads. This allows Russia to stay within the New START limits and gives it the capability to reasonably quickly increase the number of warheads if a decision is made to do so (the United States, of course, has a similar capability of its own). The actual load of missiles is hard to know, so I would (rather arbitrarily) assume that mobile Yars ICBMs carry four warheads (i.e. their full load) and silo-based ones - three. R-29RM can be downloaded to two warheads, and Bulava - to three. With bombers counted as one warhead each, this gives a total of 1531 deployed warheads, of which 930 are on ICBMs, 544 on SLBMs, and 57 are on bombers.

The earlier post about the status of the space-based segment of the Russian early-warning system got some media attention, which led colleagues to question my conclusion. And they may have a point - it may be a bit early to write these satellites off.

The earlier post about the status of the space-based segment of the Russian early-warning system got some media attention, which led colleagues to question my conclusion. And they may have a point - it may be a bit early to write these satellites off.

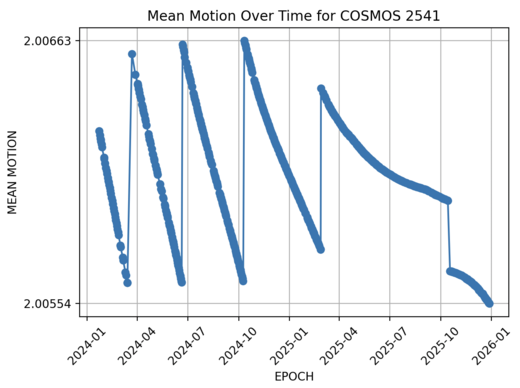

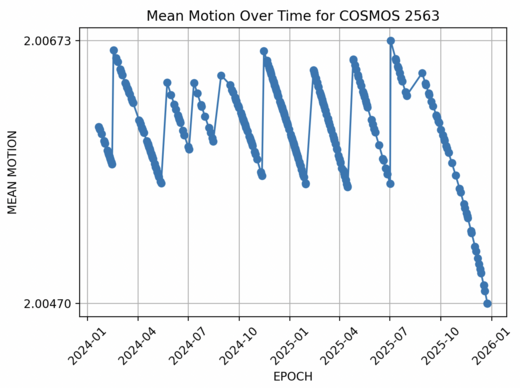

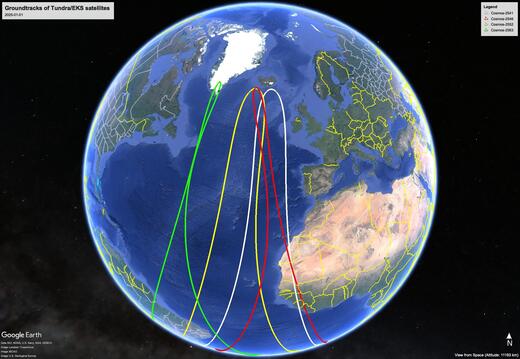

I was looking at the mean motion (the number of revolutions a day), which was a very good indicator of a working status of satellites of the earlier generation. The old Oko satellites had to be rather meticulous about station keeping as they were detecting missiles against the background of space (see this article for details). Tundra satellites apparently have true look-down capability, so they are more flexible with their orbits. Bart Hendrickx has a great overview of the Tundra/EKS satellites.

Since the notion of a station is different for Tundra satellites, the fact that we don't see standard orbit corrections does not necessarily tell us that the satellite stopped functioning. Jonathan McDowell noted that apogee longitudes of the four most recently launched satellites - Cosmos-2541, Cosmos-2546, Cosmos-2552, and Cosmos-2563 - haven't changed much--unlike those of Cosmos-2510 and Cosmos-2518, which are clearly off station.

Scott Tilley made a similar observation, also looking at apogee longitudes. He noticed, though, that starting around September 2025 all four satellites are shifting their apogees west. Since all four started the movement at the same time, Scott suggested that it's a planned maneuver to take satellites to a station that is easier to maintain, rather than a sign of dysfunction. Furthermore, he registered radio activity consistent with historical on-orbit operations and noted that there are no signs of uncontrolled behavior.

These are fairly convincing arguments, so it's quite possible that I jumped the gun in declaring the satellites non-operational. But maybe not--my understanding is that station-keeping for these kinds of orbits is a rather delicate process and a failure to perform distinct regular maneuvers is a sign that a satellite is not quite well. The groundtracks (see the image) also do not quite suggest a healthy constellation. But maybe that's because I've seen too many graphs of Oko satellites' mean motion. The current constellation is different. I guess the situation will be clearer in a few months.

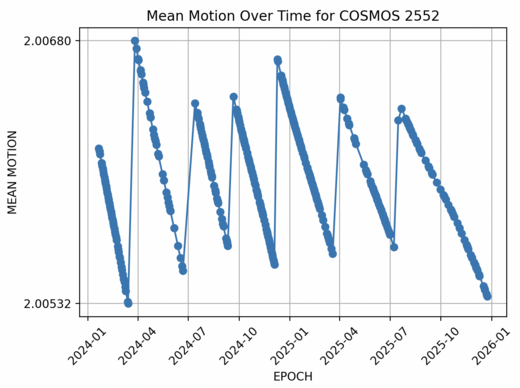

Orbital data suggest that as of the end of 2025 Russia may have only one functioning early-warning satellite of the Tundra type. This is a significant decline from the situation in March 2025, when three satellites of the constellation - Cosmos-2541 (launched in September 2019), Cosmos-2552 (November 2021), and Cosmos-2563 (November 2022) - appeared to be operational.

Orbital data suggest that as of the end of 2025 Russia may have only one functioning early-warning satellite of the Tundra type. This is a significant decline from the situation in March 2025, when three satellites of the constellation - Cosmos-2541 (launched in September 2019), Cosmos-2552 (November 2021), and Cosmos-2563 (November 2022) - appeared to be operational.

Now it appears that for Cosmos-2541, the orbit correction maneuver successfully conducted in March 2025 was the last one. Another satellite of those three, Cosmos-2563, appears to have failed at some point after the last successful maneuver in July 2025. Images below show the changes in mean motion that testify to the failures.

The only satellite that doesn't show clear signs of failure is Cosmos-2552, launched in November 2021. However, based on recent patterns, it should have performed an orbit correction sometime in November 2025 (see the main image in the post). But it is too early to say that Cosmos-2552 has ended its operations.

I should note again that the apparent loss of early-warning satellites is not necessarily a cause for alarm. Russia does not rely on the space-based segment of its early-warning system to the extent the United States does. For a discussion, see this 2015 post or my Science & Global Security article.

Oreshnik is an elusive missile. It shows up in various statements and there are some pretty tangible signs of its existence, but it is still not quite clear what the actual status of the missile is.

Oreshnik is an elusive missile. It shows up in various statements and there are some pretty tangible signs of its existence, but it is still not quite clear what the actual status of the missile is.

The most notable recent appearance of Oreshnik was in the Belarusian leader's 18 December 2025 address, in which he announced that Oreshnik was delivered to Belarus on 17 December 2025 and that it is "being placed on combat duty." Is it really?

My take is that there are reasons to be skeptical. Yes, there is strong evidence of preparations for the deployment, such as the potential deployment site found by Jeffrey Lewis' team (and confirmed by US intelligence). But there are also reasons not to read this evidence too literally, at least at this point in time.

This post is an attempt to collect what we know about Oreshnik to see how various pieces of the story fit together.

The name Oreshnik first appeared on 21 November 2024, when Russia used this missile to strike the Yuzhmash plant in Ukraine. (Here is a video of warheads hitting their targets.) In a special televised address the president of Russia described the strike as a test of a medium-range "non-nuclear hypersonic ballistic missile."

The missile was launched from Kapustin Yar, which is about 800 km away from Yuzhmash. This means that it is indeed a medium-range missile. Note that the reason it was described as a test is that technically the Russian INF moratorium proposal was still on the table. Apparently, the (not quite convincing) logic was that a test is different from deployment, so it would not violate the moratorium. Speaking at a meeting with designers on 22 November 2024, the Russian president confirmed the very narrow reading of the moratorium when he said that Oreshnik is only one of "a whole line of medium- and shorter-range systems." Nevertheless, the framing of the launch as a test was an interesting detail.

According to the report of the commander of the Strategic Rocket Forces at the 22 November 2024 meeting, the missile was developed in accordance with the presidential decision of July 2023. It appears that the missile was tested at least twice before November 2024 - in October 2023 and June 2024 (MilitaryRussia.ru citing a report by the Ukrainian Main Intelligence Directorate).

The Pentagon assessed that the missile was based on RS-26 Rubezh. The Pentagon spokesperson also said that "the United States was pre-notified briefly before the launch through nuclear risk reduction channels." Technically, since the missile was not a true ICBM, Russia was not under an obligation to send a notification, but it apparently decided to do so to avoid potential misunderstanding. If the missile is indeed based on RS-26, its signature during the boost phase would be very similar to Yars (since RS-26 was said to be based on RS-24 Yars). One can never be too careful. The Kremlin spokesman later said that the notification was "an automated warning [that] was sent 30 minutes before the launch." This is most certainly an error - these notifications are not automatic, and by all indications the warning was sent about 24 hours in advance, as required by the US-Russian agreement. We know that rumors of an upcoming ICBM launch were circulating in Ukraine the day before the strike.

The Belarusian involvement in the Oreshnik story started in December 2024. After a bilateral meeting on 6 December 2024, the president of Belarus asked for the missile to be deployed in Belarus (with a condition, though - that "the targets for these weapons" be determined by Belarus). The Russian president responded that such a deployment "is feasible." He also noted that it would be possible after the serial production of these missiles "is ratcheted up" and they are deployed with Russia's Strategic Rocket Forces (RVSN). Moreover, the Russian president suggested that even though the missiles will be operated by RVSN, it would be up to Belarus "to identify the targets."

This kind of targeting arrangement does not look particularly realistic and suggests that something different is going on here. The exchange clearly followed the pattern that had been established earlier regarding the deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus. The Belarusian leader makes bold statements and Russia plays along, especially during joint appearances.

A few days after this exchange, on 16 December 2024, the president of Russia said in an address to the Ministry of Defense that the serial production of Oreshnik "should begin in the near future." It's notable, though, that the Russian president did not mention the plan to deploy these missiles in Belarus (although he did say that these systems will be used "to protect Russia and our allies' security").

This pattern will persist through the entire year. While the president of Belarus has been constantly mentioning the deployment plan, his Russian counterpart has been more reserved. With the notable exception of joint appearances. Note, though, that he never seems to volunteer any details, opting to confirm the words of the Belarusian president. For example, at a meeting in August 2025, the Russian president confirmed that the site for the deployment in Belarus had been selected and that the missiles would be delivered by the end of the year.

At the same August meeting, the Russian president said that the industry had produced the first serial production system, which "has already been delivered to the troops." A few days later, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement that formally withdrew the INF moratorium proposal made in October 2020. The statement, however, did not mention Oreshnik or any other specific system, noting instead that "decisions on the specific parameters of response measures will be made by the leadership of the Russian Federation" based on the analysis of the situation.

News about Oreshnik continued to come mostly from Belarus. However, the deployment announcement on 18 December 2025 came after the president of Russia said at a meeting at the Ministry of Defense on 17 December 2025 that "[b]y the end of the year, the medium-range missile system armed with the Oreshnik hypersonic missile will be placed on combat duty." Notably, he said nothing that would suggest that the missiles would be deployed in Belarus. Neither did he mention Oreshnik in Belarus when asked directly during the end-of-the-year press conference. The Minister of Defense, who spoke after the president, also said nothing about Belarus when mentioning Oreshnik. The Chief of the General Staff, who spoke the next day at a meeting with military attachés, told them that "a brigade has been formed equipped with a new medium-range missile system, Oreshnik."

I would say that "a brigade has been formed" is pretty far from "missiles have been delivered to Belarus where they are entering combat duty." I am far from suggesting that Oreshnik is a phantom missile - the evidence suggests that it is not. But at the same time, I do believe that we should be very skeptical about reports of its deployment in Belarus. I find it very hard to believe that the Strategic Rocket Forces, which are expected to operate the missile, will be happy about being stationed outside Russia. Besides, the case for the military utility of the deployment is virtually non-existent. Note that the Krichev-6 site is literally seven kilometers from the Russian border (see the image above).

The "division of labor" between Russia and Belarus regarding virtually all news about Oreshnik also makes me suspicious. We have seen a similar pattern with nuclear weapons - Russia lets Belarus make all kinds of statements about them and even builds a storage facility that should be capable of accepting these weapons if necessary. But there has been no confirmation of the deployment from the Russian side and there are no signs of weapons being actually delivered to Belarus (I believe they will never be deployed there, but that's a topic for another post). The same seems to be the case with the missile base. The infrastructure, of course, could become useful someday, but we are not there yet. For the moment, it appears that both sides are involved in a rather strange political spectacle. I still hope that it will not involve actual movements of missiles (not to mention nuclear weapons), but we cannot exclude that it will.

UPDATE: On 30 December 2025, the Ministry of Defense announced that the first Oreshnik unit was deployed in Belarus. The MoD released a video that showed a ceremony of a unit beginning the combat duty. The site was later confirmed to be Krichev-6, identified earlier. The video, however, does not show any launchers or missiles.

Russia appears to have made another attempt to launch a Yars ICBM from Plesetsk. It issued a NOTAM notification with a window opening at 6:00 UTC on 25 December 2025. It probably notified the United States about the upcoming launch: the United States dispatched an RC-135 Cobra Ball aircraft to monitor the launch. The aircraft returned to the base after an 18-hour flight, but the launch did not take place on the 25th as the NOTAM was not cancelled. Cobra Ball flew another mission on December 26th (taking off around 2:00 UTC). The NOTAMs were cancelled around 08:20 UTC on December 26th and the aircraft returned to the base.

It is not clear whether a launch took place on the 26th or was cancelled as was apparently the case with the attempt in early December. Given that no reports about the launch appeared in the Russian media, a cancellation is more likely.

In the traditional 17 December interview marking the anniversary of the Strategic Rocket Forces (established on that day in 1959), commander Sergey Karakayev reported that his force completed the deployment of Yars missiles in the silos of the missile division in Kozelsk. (Video of the deployment by Zvezda TV.)

In the traditional 17 December interview marking the anniversary of the Strategic Rocket Forces (established on that day in 1959), commander Sergey Karakayev reported that his force completed the deployment of Yars missiles in the silos of the missile division in Kozelsk. (Video of the deployment by Zvezda TV.)

This brings the number of silo-based Yars missiles in the 28th Missile Division to 30. The missiles are deployed in three regiments - 74th, 168th, and 373rd. The older three regiments of the division - 119th, 214th, and 372nd - were disbanded around 2007-2009. Here is the kmz file with silo coordinates.

The decision to keep three regiments and use them to deploy "new-generation missiles" was made in 2008. In 2011, the Rocket Forces announced that these silos would be used to deploy Yars missiles. The first two missiles were deployed in 2014.