It looks like we are back to the discussion of the merits of the Megatons to Megawatts program (aka HEU-LEU agreement). A quite confused article in the New York Times, which threw together START, HEU, missiles, and a lot of other things, quoted U.S. officials as saying that the United States and Russia are discussing a so-called HEU-2 deal, which would presumably extend the current down-blending effort beyond 2013, when the current program is supposed to complete down-blending the initial 500 tonnes of HEU.

I sure hope that they aren't.

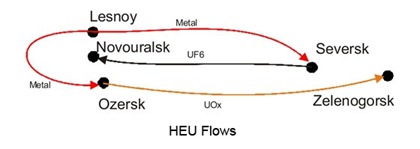

From the security point of view, the deal make absolutely no sense, to put it very mildly. I wrote about it in a Bulletin column about a year ago - the program is constantly creating unnecessary additional risks by hauling about 30 tonnes of HEU annually across Russia several times in many shipments. The chart below (adapted from an IPFM report) shows the current HEU flows:

I simply don't see how it could be that shipping tens of tonnes of HEU metal, oxide or UF6 between all these places is a contribution to security of that HEU. Especially if we take into account that the program does nothing to eliminate whatever security problems may exist where the material is coming from - at warhead storage sites or at centralized fissile material storage facilities.

I simply don't see how it could be that shipping tens of tonnes of HEU metal, oxide or UF6 between all these places is a contribution to security of that HEU. Especially if we take into account that the program does nothing to eliminate whatever security problems may exist where the material is coming from - at warhead storage sites or at centralized fissile material storage facilities.

As I wrote a year ago, the program played an important and useful role in the past. But the only danger that this program is reducing now is that of Russia's making new nuclear warheads out of that HEU. I am all for elimination of warheads and weapon-usable materials, but I would hope that we could find a way of doing so that would be less insane than shipping those materials back and forth.

I still believe that a much better way of dealing with the materials would be to keep them in secure storage for the moment - warheads in the custody of the 12th Directorate, and materials - in centralized storage, at Mayak or elsewhere. The material there is much more easier to secure and account for than that same material hauled to across the country in bulk form. At some point the material would have to be eliminated, of course, but I don't see why this cannot wait until Mayak has all the required facilities.

Luckily, the down-blending deal does not make any sense for Russia from the commercial point of view. Rosatom doesn't like it anymore (it's not getting the money directly as it used to in the early days of the program), so it has been resisting the attempts to extend the deal for some time now. I hope Rosatom will be able to fight off new attempts as well.

As for the new U.S. administration, if it believes it has some political capital to spend with Rosatom, I would certainly hope it would not waste it promoting a program that makes all of us less secure.

Comments

Background Twitter discussion re Megatons to Megawats ...

intlsecurity: RT @russianforces: Megatons -> Megawatts program still doesn't make sense | Good points; but I think benefits outweigh risks.

russianforces: What are the benefits of MtM? That a storage site somewhere will have 1000 wh instead of 1500? How this is a benefit?

intlsecurity: Re MtM: yes, 1000 wh is better than 1500. I agree w you short term, but long term security increased. Clearly, an irony.

russianforces: The logic of this completely escapes me. How 1000 is better than 1500? And why all the MtM shipping risk is a reasonable price?

russianforces: I agree that the program made sense back when it started. It doesn't anymore.

=====

To continue the discussion ...

I'm not sure I agree that Russian material in transit is less proliferation secure than in storage. I could argue both sides in the Russian case. But, for the sake of argument, let's assume that every transport of a warhead or container of material increases the proliferation risk over the material remaining in centralized storage.

From a purely proliferation point of view, fissile material in weapons is more secure than when it is removed from warheads. We could take that logic a step further and say that, by far, the most secure material is in deployed warheads. This is the "irony" to which I referred in my tweet. Is that what we want?

You wrote in the Bulletin: "The downside of [the material-kept-in-warhead-form] option is that more nuclear warheads would be around longer, but that's the price of securing the material." This appears to be our fundamental disagreement.

Fewer warheads is, inherently I would argue, a “good” thing. So yes, 1,000 is better than 1,500. To alter the terms of reference here, from a US national security perspective, the US is more secure when there are fewer warheads in the world that are capable of reaching the US homeland. I'm sure the Europeans, Chinese, and others would agree. I am willing to trade some theoretical threat (of potential proliferation) in favor of reducing a existential one (of stored, deployable warheads).

What we're talking about, as I understand it, are 1-2 additional shipments imposed under MtM that would not occur during a typical dismantlement process.

You point out that "times have changed" to argue that the Russian organizations no longer need the income from the MtM program. While those organizations may now more reliably count on the government's central budget, times have also changed in the sense that the internal security threats may not be as dire as those posed in the 1990s. So, while transporting the material may be inherently less secure than keeping it in storage, the extant threats to those shipments have decreased since the program's inception.

If, then, we desire warhead reductions, and the transportation required for MtM processing is manageably riskier than for any other dismantlement process, then the MtM program offers additional benefits. For one, it is a process through which the US and Russian business communities can work together. The US and Russia need more ways to work cooperatively with each other, not fewer. Burning the material in US power reactors as fuel is, to me, preferable to leaving the material in Russia and keeping it available for possible non-civilian use.

To respond to your remarks that you supported the program initially, but that it no longer makes sense, I believe that it makes sense now as much as it ever did. US-Russian relations remain troubled, and the new US administration has not made the kind of progress that many hoped. START+ is not going to magically alter that course. There are too many structural problems with the relationships. I'll repeat, therefore, an argument that we in CTR were making in the early 1990s: if we have an opportunity to cooperatively reduce the direct threat that those warheads pose to the US, let's do what we can to accelerate that process while we still can.

Rather than ditching the program, are there ways of improving the process to make proliferation less likely? You offered one possible solution: "Another option would be to consolidate all activities at Seversk, eliminating all unnecessary transfers." Perhaps there are others.

Note that none of my arguments deal with the issues of economic/market sensibilities or Russian internal politics. Those are separate issues, aside from whether MtM makes sense from national security, international security, or nonproliferation perspectives.

My perspectives are admittedly American. A Russian perspective would, naturally, differ. I am not in favor of nuclear warhead reductions at any cost. But, I am in favor of nuclear warhead reductions in a responsible manner. Transporting the material is a necessary step in any dismantlement process. So, let's improve upon a program that is cooperatively reducing an intrinsic threat.

It doesn’t really matter whether the material in transit is less or more secure than the one in storage. The point is that unless some material remains in storage, any transfer adds to the risk – whether it low or high. This additional risk may be tolerated in some circumstances, e.g. when you are cleaning out a storage site completely, but not in today’s MtM program – as far as I know, no storage facilities are being eliminated.

As I understand, you meant to say that “fissile material in weapons is more secure than when it is not removed from warheads.” I think we agree on that. I also agree that the fewer warheads the better. But there is nothing “inherently good” about eliminating warheads at any cost, which is exactly what MtM program does today. I’m sure nobody would argue that warheads should be eliminated by giving out their fissile material components on the street, even though this would certainly result in fewer warheads capable of reaching the U.S. I know that the whole program is driven by this particular logic – the fewer warheads there are in Russia the better – but I don’t agree that this approach makes anyone (including the U.S.) more secure today.

If people are so much concerned about the numbers of warheads that can reach them, I’m sure there are ways to disable warheads in storage. In fact, I think the warheads in storage are disabled for all practical purposes anyway – they need delivery systems and most of them are probably past their service lives. What’s the rush to move them out and expose the material to additional risks? Then, I don’t quite agree that transportation is an inevitable part of the process (certainly not that of HEU oxide). It is true only if you try to eliminate the material quickly, the risks be damned. I'm sure things could wait until Russia builds all necessary facilities at Mayak or in Seversk.

One more thing that I find particularly problematic is that in the process fissile materials are converted to bulk form – oxide powder, UF6 – in which they are fundamentally more difficult to keep track of than if they stay in “countable” warheads or components. If we are talking about 30 tonnes of HEU annually, the accuracy of tracking the inventory should be on the order of fractions of percent.

I agree that there is a value in cooperative work and that would have been an important benefit of the program (as it indeed was in the past). But Russia doesn’t want to continue this program. The push to continue down-blending creates quite a bit of ill will and mistrust and eventually makes it difficult to implement other programs, the ones that make sense.

Two articles appeared in the Russian press recently that prompted me to return to this discussion with my friend, Pavel. Those articles are below, and I'll comment on them in a moment.

First, a couple of remarks on your last entry above. I certainly do not favor reductions "at any cost." But, I am willing to trade tolerable additional short-term risk in favor of significantly greater long-term security. That, I believe, fairly describes the benefit of the MtM program.

Regarding the Argumenty Nedeli article below, I appreciate that many Russians feel they got a raw deal on the price, and that they have concerns about exporting a strategic resource. But, it's hard to get past the hyperbole.

Finally, the Moscow Times oped is not only in favor of MtM, but advocates a much broader agenda for cooperation in this area. START, MtM, the 123 Agreement, and the commercial sectors are interconnected to some degree, but I'm not sure it's a good idea make those linkages explicit. And the contest that is heating up for the Indian market will complicate all of these matters. I tend to prefer discrete, definable programs that can be justified and implemented on their own merits.

But, back to MtM, I will in principle support programs like this that have long-term threat reduction benefits through cooperative processes ~ as opposed to the inherently adversarial arms control process. I'd like to think the parties could find a way to make the program secure and mutually beneficial, rather than discard it.

~~~~~

Playing the Nuclear Accordion. American Nuclear Power Plants Await New Batch of Fuel from Russia

by Nadezhda Popova

Argumenty Nedeli Online, 26 Nov 09

The United States and Russia are secretly working on a new contract envisioning the reprocessing of Russian nuclear warheads into fuel for American nuclear power stations. This contract is linked to the new agreement on the limitation of strategic offensive arms (START). The number of missiles that Russia will give up under the new START treaty will have a direct impact on the number of warheads reprocessed in the United States and the volume of energy produced.

The New York Times writes about this, citing a source in the Federal Atomic Energy Agency in Washington.

Meanwhile, Dmitriy Medvedev and Barack Obama will meet in early December to sign a new treaty on the limitation of strategic offensive arms. What kind of upsets or surprises might there be? We have already received one surprise: Barack Obama, who only recently was advocating only "green" energy, has suddenly become smitten by "peaceful" nuclear energy. And has started talking about a nuclear renaissance in the United States. Where has this come from?

Metamorphoses in the State of Florida

But let us return to Washington. "By 2014 one American nuclear power plant in every five will be operating on Russian uranium," was a slogan that I saw in Washington during an assignment to the United States on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Alliance for Nuclear Security (April 2007). At that time American nuclear scientists were already telling us Russian journalists about the specific fuel being used by nuclear plants in Michigan, Nevada, and Pennsylvania -- fuel extracted from Soviet nuclear warheads.

The curious thing is that in 2007 there was no talk about a renaissance of nuclear energy in the United States. On the contrary, the only thing that they were saying was that it was necessary to say goodbye to nuclear power plants as it was still unclear what should be done with irradiated nuclear fuel. But then we get yet another surprise!

"On 16 October 2008 the Florida State Public Service Commission allowed the state's two biggest energy companies to take more than $270 million from taxpayers as part of a mechanism of advance payments for the construction of nuclear power plants," nuclear scientist Valeriy Volkov told Argumenty nedeli. "The plan is to install a fifth and sixth power unit at the Turkey Point nuclear power plant. And to increase the capacity of Turkey Point's third and fourth power units. The two new reactors at Turkey Point will be commissioned in 2018-2020."

The Public Service Commission also adopted a positive decision on the construction of new units at the Levy County nuclear power plant and on increasing the capacity of the current reactor at the Crystal River nuclear plant. The first and second units at the Levy County nuclear plant will be commissioned in 2016 and 2017.

But this is still not the end of the breathtaking news. Twelve US energy companies have informed the Nuclear Regulatory Commission of their plans to seek licenses for the construction and operation of 23 new nuclear reactors.

All these "babies" require intensive feeding. With what? With low-enriched uranium. Where is it to be acquired in such quantities?

American energy companies are expecting good news after the meeting between Medvedev and Obama: American nuclear power plants -- old and new alike -- badly need new nuclear fuel from Russian missiles.

At the Moscow summit in July 2009 Dmitriy Medvedev and Barack Obama signed a document of intent to almost halve the number of nuclear warheads -- to 1,500-1,675 units -- and also the number of delivery vehicles for them -- to 500-1,100 units.

From Argumenty nedeli's files

The START I treaty signed in 1991 obliged Moscow and Washington to cut their strategic nuclear forces from 10,000 warheads on each side to 6,000 and to cut the number of delivery vehicles for them to 1,600 on each side.

The nuclear lobby

But why has the United States suddenly decided to build so many nuclear facilities?

"One of the main reasons is concern about global warming," Professor Igor Ostretsov, doctor of technical sciences, considers. "It is not easy to rapidly introduce energy-saving technologies. Whereas nuclear power stations generate minimal atmospheric emissions in comparison with thermal stations. The second reason is that there is a very strong nuclear lobby in the United States."

But these are not the only reasons. The United States needs to obtain new fuel from Russia for its old and new nuclear power plants. They do not have much of the weapons-grade uranium that has gone to the United States since the scandalous "uranium deal." In 1993 Russia undertook to sell 500 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium for a ridiculous price. And it is indeed selling it. The United States has already taken delivery of more than 350 tonnes of Russian weapons-grade uranium for peanuts, to use a figurative expression....

On the subject of the 10,000 warheads

Despite the fact that more than 16 years have passed, the uranium deal remains a very hot topic to this day. We would remind you that 18 February 1993 saw the signing of the Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the United States of America Concerning the Disposition of Highly Enriched Uranium Extracted from Nuclear Weapons. The program became known as "Megatons to Megawatts." Russia undertook to sell the United States 500 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium over a period of 20 years at a price of 11.9 billion "greenbacks."

The reprocessing is handled by the US Enrichment Corporation company. It has already managed to reprocess more than 10,000 warheads. The agreement expires in 2013. But despite the fact that the "Megatons to Megawatts" agreement only expires in four years' time, it is being linked to the new START agreement. The United States badly needs new nuclear fuel from Russia ahead of its nuclear renaissance.

"But we have already sold such a quantity of reactor-grade uranium as would suffice Russia for many years," Doctor of Technical Sciences Ivan Nikitchuk, chairman of the (1997) parliamentary commission on the "uranium deal," told Argumenty nedeli. "This uranium that has been dispatched to the United States is very high-quality raw material. And it needs to be diluted by a factor of 20. This is a totally unique operation that only Russian nuclear scientists have mastered. It is known as 'impoverishment.'"

The 500 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium that Russia has to supply to the United States would suffice to operate all the nuclear power plants in Russia and the CIS for 30 years.

Notes in the margin

There are currently 140 nuclear reactors operating in the United States. Some 45 percent of the reactor fuel consists of radioactive material from Russia. It accounts for around 20 percent of electricity consumption in the United States.

Unilateral nuclear disarmament

Novosibirsk physicist Lev Maksimov is convinced that the actual value of the uranium deal is $8 trillion. The deal was underpriced by a factor of almost 1,000.

"The real intention of the 'uranium deal' is to secure Russia's unilateral nuclear disarmament by depriving it of stocks of weapons-grade uranium," the scientist feels.

But the word is that there are enormous stocks of highly enriched uranium concentrated in Russia. And that the sale of some 500 tonnes will not impact on issues related to the safeguarding of national security.

"The crux of this manipulation is a substitution of concepts," Lev Nikolayevich explains. "The percentage of isotope 235 in natural uranium is only 0.71. Only rich countries with highly complex technologies are capable of extracting, purifying, and collecting these fractions in such a way that the percentage can be increased to 90-95 percent. Documents on the history of the nuclear project that have been declassified in the United States state that the United States, having spent $3.9 trillion on the development of nuclear weapons from 1945, was able to produce only 550 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium.

And the Americans are saving their own uranium. And demanding our Russian uranium.

It transpires that we have sold our own reserves of weapons-grade uranium for a knockdown price and are continuing to dispatch a very precious strategically important material at a knockdown price.

Let us listen to what US President Obama has to say. He is telling his people very interesting things:

"We are standing on the threshold of a nuclear energy renaissance. This is evidenced by the announcement of several orders for the construction of new nuclear power plants. National laboratories are working with the country's universities and industry on the next generation of nuclear energy systems, which will be even more economical, safe, and sustainable with a closed-loop fuel cycle making it possible to burn significantly more nuclear fuel."

Read -- Russian nuclear fuel....

From Argumenty nedeli's files

The uranium deal (1995-2008)

1995 -- 244 warheads destroyed, 6.1 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

1996 -- 723 warheads destroyed, 18.1 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

1997 -- 1,257 warheads destroyed, 31.5 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

1998 -- 2,021 warheads destroyed, 50.6 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

1999 -- 2,991 warheads destroyed, 74.3 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2000 -- 4,453 warheads destroyed, 111.5 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2001 -- 5,654 warheads destroyed, 141.5 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2002 -- 6,855 warheads destroyed, 171.5 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2003 -- 8,058 warheads destroyed, 201.6 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2004 -- 9,260 warheads destroyed, 231.7 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2005 -- 10,466 warheads destroyed, 261.8 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2006 -- 11,673 warheads destroyed, 291.9 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2007 -- 12,885 warheads destroyed, 322.2 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

2008 -- 14,090 warheads destroyed, 352.3 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium sold.

As of 31 December 2008 Russia had sold 352.3 tonnes of weapons-grade uranium. The deal had been 64.4 percent fulfilled.

~~~~~

http://www.themoscowtimes.com/opinion/article/391187.html

From Megatons to Megawatts

10 December 2009

By Gregory Austin and Danila Bochkarev

Russian nuclear fuel is keeping the lights on in California’s homes supplied by the Avila Beach and San Clemente nuclear power plants. Just less than 20 percent of all of the U.S. state’s electricity production comes from nuclear power. But California is not the only state in which Russian nuclear fuel is being widely used for power generation. According to the U.S. Energy Department, in 2007 about 40 percent of nuclear fuel used by the U.S. nuclear power sector came from Russia. In May, Chicago-based Exelon and other U.S. utilities signed a key new agreement with Moscow-based Techsnabexport, or TENEX, allowing direct commercial sales of Russian nuclear fuel to the U.S. market. Previously, U.S. anti-dumping laws only allowed the selling of the uranium recovered from dismantled Soviet nuclear weapons.

Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev confirmed their commitment to resetting the U.S.-Russian strategic partnership during the Moscow summit in July. A good place to jump-start this process is by strengthening cooperation in the nuclear power sector.

Russia and the United States should take a joint leadership role in supporting the global nuclear industry and managing a safer “nuclear renaissance.” For example, both countries should work more closely together to establish an international nuclear fuel bank. A fuel bank based on the proliferation-resistant, closed fuel-cycle solution for civil nuclear energy is a point on which both countries can agree. Moreover, both sides can bring to the partnership valuable expertise in nuclear power generation.

The United States and Russia should build on these foundations by promoting technical cooperation between their respective civil nuclear industries. This would significantly advance their national energy security and bring tangible commercial benefits. Both countries would benefit from demonstrating stronger joint leadership to promote multilateral civil nuclear energy frameworks.

Aside from the benefits for energy security, bilateral cooperation in this field could also help to rejuvenate stalled U.S.-Russian dialogue on other matters of global strategic importance.

Unfortunately, the civil nuclear agenda has often been held hostage, especially under the past administration, to serious divergences between Moscow and Washington over larger global strategic issues, including Iran. There are profound differences in opinion between Russian and Western security experts and elites as to the range of cooperative possibilities in the nuclear energy relationship.

But there is reason for optimism as the stage is already set for closer cooperation between the United States and Russia. In an April 1 joint statement by the Group of Eight, the U.S. and Russian presidents called for further bilateral nuclear cooperation. “Together, we seek to secure nuclear weapons and materials, while promoting the safe use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes,” Medvedev and Obama stressed in the statement.

The United States and Russia share a vision of a sustainable energy future less reliant on dwindling and environmentally damaging fossil fuels. A joint U.S.-Russian initiative on civil nuclear energy would be a step closer to this goal.

The two countries need to make commitments that go beyond their current strategies. For example, Washington and Moscow should resume the process of ratifying the United States-Russia Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, also known as the 123 Agreement. In fact, ratification of the 123 Agreement is an indispensable precondition for conducting joint scientific experiments and developing a full-scale technological and commercial partnership.

Moscow and Washington should also create a bilateral intergovernmental commission to define technical parameters for civil nuclear cooperation and commit to a firm deadline — for example, by the end of 2010 — for making a joint proposal on an international fuel bank that effectively merges the existing national proposals.

They should also establish a firm framework for transferring affordable and proliferation-resistant technology to developing countries. This can be done through a multilateral nuclear technology knowledge bank based on public-private cooperation under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Furthermore, the United States and Russia should use the knowledge bank to develop a set of political and business incentives that promote a clear and rapid move to new power-generation solutions, such as thermo-nuclear fusion.

Civil nuclear energy can play the same role for U.S.-Russian relations that coal and steel played for German-French relations after World War II. A nuclear energy partnership can foster technical cooperation on a practical, functional and nonpoliticized basis, while simultaneously promoting global security.

[Gregory Austin is vice president of program development and rapid response and Danila Bochkarev is associate for energy security at the EastWest Institute. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the EastWest Institute, its staff or board.]

Chuck, thank you for posting these. But first on your remark about a trade of "tolerable additional short-term risk in favor of significantly greater long-term security". The problem with this position is that I don't see what the long-term security benefits are. Russia with only 1000 tonnes of HEU (as opposed to 1500)? Again, I would agree that elimination of all HEU and Pu (including the U.S. material) is a good long-term goal. My point is that the MtM program is a wrong way of getting there.

On the articles, the Argumenty one quotes the wrong kind of people - there is a fringe faction that argues that HEU cost trillions or something. My sense is that people at Rosatom understand that things cost what you can get on the market at the time you brought them there and although they certainly would like to see a better deal on HEU there are no particularly hard feelings there. However, I would not be surprised if they see HEU simply as an asset - separative work already done. So, I would expect them to resist any further downblending just for that reason. If one side does not like the deal and feels forced into it, the deal would probably not qualify as a "cooperative processes". (Speaking of "forced" - here is, for example, a language introduced by Domenici in May 2008. And that, I understand, is a mild version of the original much harsher proposal, which said that Russia should have no access to the market unless it agrees to further downblending.)

I think the EWI folks make a good general point, although they seem unaware that the 123 agreement does not require ratification. There are quite a few programs that Russia would be ready to work cooperatively with the U.S. I wrote about this last year. If a "cooperative program" is a goal, Russia and the U.S. can, for example, work on safeguarding centrifuge facilities. MtM used to be a program like that at the time. But it is not anymore.

We ought not forget that today’s conditions are dramatically different than those in which Megatons to Megawatts was conceived. The initial idea came from Thomas L. Neff in an op-ed published in The New York Times on October 24, 1991. This was after the August coup attempt and before the Soviet collapse. Neff’s piece, titled “A Grand Uranium Bargain,” noted the chaos at the time, with republics going their own way. There were strategic weapons in Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan as well as Russia. A large number of tactical nuclear weapons were being withdrawn to Russia from Eastern Europe and other republics. Neff’s point was that it was better to channel the uranium from all dismantled warheads into a useful civilian project rather than take a chance on other outcomes. He said:

“The warheads contain substantial amounts of valuable material that can be processed for use in commercial nuclear power plants. It may be advantageous for the U.S. to buy or barter for such materials and turn them safely to commercial use. This can be done in ways that protect Western and Soviet commercial and security interests.

“If we do not obtain the material, agents in the former Soviet Union, perhaps uncontrolled by central authority, may flood commercial nuclear fuel markets with material from arms programs or even seek to sell weapons grade materials to highest bidders.”

At the time, the Soviet central government was losing power to the republics, with Yeltsin and Russia gaining a dominant position. If I recall correctly, Viktor Mikhailov, who was made the minister of atomic energy by Yeltsin the following spring, was in favor of the deal because of the revenue it would bring to the cash-starved state and his powerful ministry. Also, I don’t think anyone knew in those early days how much HEU there was. Neff estimated in his op-ed 500 tons; it was only a while later that estimates rose to 1,200 tons or more. I remember that Bill Burns was asked to look into the idea of buying the uranium as part of the early SSD (Safe Secure Dismantlement) discussions, which were plagued by mistrust, and it was no easy task because no one knew how to negotiate such a deal so soon after the end of the Cold War. The diplomatic cables in the spring of 1992 show that the Russians were super-sensitive about HEU; they could barely be convinced to allow Americans to go on a tour of an LEU line at Electrostal.

My point is that the deal was conceived at a time when the state was weak, broke, Cold War suspicions still reigned, and proliferation seemed a real threat. Today, Russia is relatively wealthy, warheads have been recalled from other republics, the Fissile Material Storage Facility is completed and the Cold War is almost two decades gone.

I think the program was a smart idea when it was conceived. But there’s no harm in re-evaluating it. Here’s a question that is, in my view, just as urgent as the future of MtM: what is the status of the FMSF? Wasn’t it built so this material could be safely stored? If it is 3/4 empty, why?

I can see another reason why Russia might be disenchanted with Megatons to Megawatts - it depresses the world spot price of crude oil. Bad for business, not so?

Which is not to impute sinister motives to Russia, simply commercial motives. Hey, if Moscow reneges on MT2MW, it just increases the price of uranium and improves the economy here in the state of Colorado (where local uranium mines oscillate in and out of profitability from year to year at present).

The hard-line left here in the USA is really going to be cheesed off at Obama if there's any sincerity to that "nuclear renaissance" stuff. I'm all for it. Nuclear power (uranium, specifically) is the cheapest source of energy for electric power generation available by a factor of between two and eight, depending on this year's pricing for coal and natural gas.

As battery technology improves and the production price drops, nuclear-generated electricity could even make inroads into the motor fuel market, either for plug-in cars or as an energy source for the on-spot synthesis of hydrogen as a motor fuel. Road and Track recently published an interesting article road-testing a hydrogen vehicle on a stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway which has hydrogen filling stations available for consumers.

Of course, the increasing availability of nuclear power as a substitute for fossil fuel (maybe we can adopt "geologic fuel" as a euphemism for uranium and plutonium, since "nuclear" provokes such a knee-jerk response in some people) will be a great selling point for cap-and-trade, which is right now facing a lot of staunch opposition here in the States.

Amazing... nuclear power furthering the cause of ecology. Who'd have thunk it?